https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/images/ic/640x360/p0c7jnpy.jpg

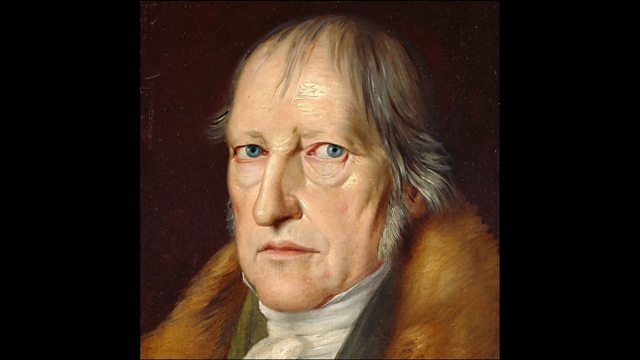

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss ideas of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770 - 1831) on history. Hegel, one of the most influential of the modern philosophers, described history as the progress in the consciousness of freedom, asking whether we enjoy more freedom now than those who came before us. To explore this, he looked into the past to identify periods when freedom was moving from the one to the few to the all, arguing that once we understand the true nature of freedom we reach an endpoint in understanding. That end of history, as it's known, describes an understanding of freedom so far progressed, so profound, that it cannot be extended or deepened even if it can be lost.

With Sally Sedgwick, Professor and Chair of Philosophy at Boston University, Robert Stern,

Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sheffield, and Stephen Houlgate, Professor of Philosophy at the University of Warwick.

Review

Having heard Russell's critique of Hegel, it was interesting to hear a very positive discussion of Hegel. I did get the impression, however, of some special pleading when it came to faults and issues with Hegel's philosophy.

1. Evolution

Evolution - Hegel's philosophy rejected evolution. He said: “it is a completely empty thought to represent species as developing successively, one after the other, in time…. The land animal did not develop naturally out of the aquatic animal, nor did it fly into the air on leaving the water.”

He also clearly could not see continuities between different forms of life, especially man and animal: "even if the earth was once in a state where it had no living things but only the chemical process, and so on, yet the moment the lightning of life strikes into matter, at once there is present a determinate, complete creature, as Minerva fully armed springs forth from the head of Jupiter…. Man has not developed himself out of the animal, nor the animal out of the plant; each is at a single stroke what it is.”

In an article, Houlgate attempts to defend Hegel by making out that Hegel had only come across Lamark and earlier ideas about evolution, and pre-dated Darwin. That's true, but earlier ideas on evolution also attacked the notion of fixity of species which we see in modern Creationism and very clearly in Hegel.

It is instructive to note , as John Wilkins, University of Queensland has shown, that Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, began his career committed to the fixity of species, but began accepting the evidence against such fixity approximately a century before Darwin's ideas were published. The difference is that Linnaeus was a meticulous observational scientist, and it is clear that Hegel is making statements which are not backed up by scientific evidence of any kind.

It is instructive to note , as John Wilkins, University of Queensland has shown, that Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, began his career committed to the fixity of species, but began accepting the evidence against such fixity approximately a century before Darwin's ideas were published. The difference is that Linnaeus was a meticulous observational scientist, and it is clear that Hegel is making statements which are not backed up by scientific evidence of any kind.

Darwin, incidentally, never claimed for himself that he was the first to use the idea of evolution, only its mechanisms. As he stated in a letter:

"No educated person, not even the most ignorant, could suppose I mean to arrogate to myself the origination of the doctrine that species had not been independently created. The only novelty in my work is the attempt to explain how species became modified, and to a certain extent how the theory of descent explains certain large classes of facts; and in these respects I received no assistance from my predecessors."

"No educated person, not even the most ignorant, could suppose I mean to arrogate to myself the origination of the doctrine that species had not been independently created. The only novelty in my work is the attempt to explain how species became modified, and to a certain extent how the theory of descent explains certain large classes of facts; and in these respects I received no assistance from my predecessors."

Darwin was an experimental scientist, who carefully collated observations, and gradually formed conclusions based on painstaking work, and thought about that evidence. He was prepared to follow the evidence. Hegel was bound by his philosophical assumptions, and clearly could not break free from them when it came to evolution, instead following in the tradition of the Great Chain of Being, where species are fixed and immutable from their conception.

2. Slavery and Africa

And Hegel was avidly quoted by those who opposed the abolition of slavery, because he saw it is an intermediate phase, not bad in itself:

“The ‘natural condition’ itself is one of

absolute and thorough injustice, contravention of the right and just. Every

intermediate grade between this and the realization of a rational State

retains, as might be expected, elements and aspects of injustice; therefore

we find slavery, even in the Greek and Roman States, as we do serfdom,

down to the latest times. But thus existing in a State, slavery is itself a phase

of advance from the merely isolated sensual existence, a phase of education,

a mode of becoming participant in a higher morality and the culture connected

with it.”

With regard to the negro, Hegel said that "They do not attain to the feeling of

man’s personality,—their mind is entirely dormant, it remains sunk

within itself, it makes no progress, and thus corresponds to the compact,

undifferentiated mass of the African land."

At this point I'd like to look at another, but lesser known scientist. Heinrich Barth Barth had been trained by professors influenced by Hegel and began with a background informed with racist perceptions. Hegel had written that: "It is in the Caucasian race that spirit first reaches absolute unity with

itself. It is here that it first enters into complete opposition to naturality,

apprehends itself in its absolute independence, disengages from the

dispersive vacillation between one extreme and the other, achieves self-determination, self-development, and so brings forth world history. It is, the concrete universal, self-determining thought, which constitutes

the principle and character of Europeans."

But Barth had the benefit of a three-year, three-continent journey along the shores of the Mediterranean when he had encountered African culture in person. As Steve Kemper noted: "He was also a scientist who tried to keep an open mind and follow the evidence before him. Part of what Barth discovered on his journey—what he was willing to let himself discover—was that Africa had a long rich history, some of it written, that was unsuspected or ignored in Europe. He recorded barbarity and fanaticism, but also scholarship, governance, culture, tradition. "

Why could Barth see things better than Hegel or Kant? Because he did not accept second hand evidence from others in formulating his records, but went out on the ground to see for himself, and was prepared to let what he saw inform and change his views.

3. Odds and Ends

It was interesting to listen to this program, but the obscure nature of Hegel's own texts was not mentioned, not where he really came adrift in his thinking. One thing which came out which is palpably wrong is the is the idea of progress. While he saw this as being troubled, and having setbacks, he nevertheless has an idea of history leading somewhere. He's not alone there - the Whig historians did the same in their own way with histories of Britain. But there is really no basis for it apart from wishful thinking.

Here's a few choice examples of his obscure language:

"Spirit . . . has shown itself to us to be neither merely the withdrawing of self-consciousness into its pure inwardness, nor the mere submergence of self-consciousness into substance, and the non-being of its difference; but Spirit is this movement of the Self which empties itself of itself and sinks itself into its substance, and also, as Subject, has gone out of that substance into itself, making the substance into an object and a content at the same time as it cancels this difference between objectivity and content. . . . Spirit, therefore, having won the Notion, displays its existence and movement in this ether of its life and is Science."

No comments:

Post a Comment